G u m b a l l P r o j e c t - T h e P u l l m a n S t r i k e

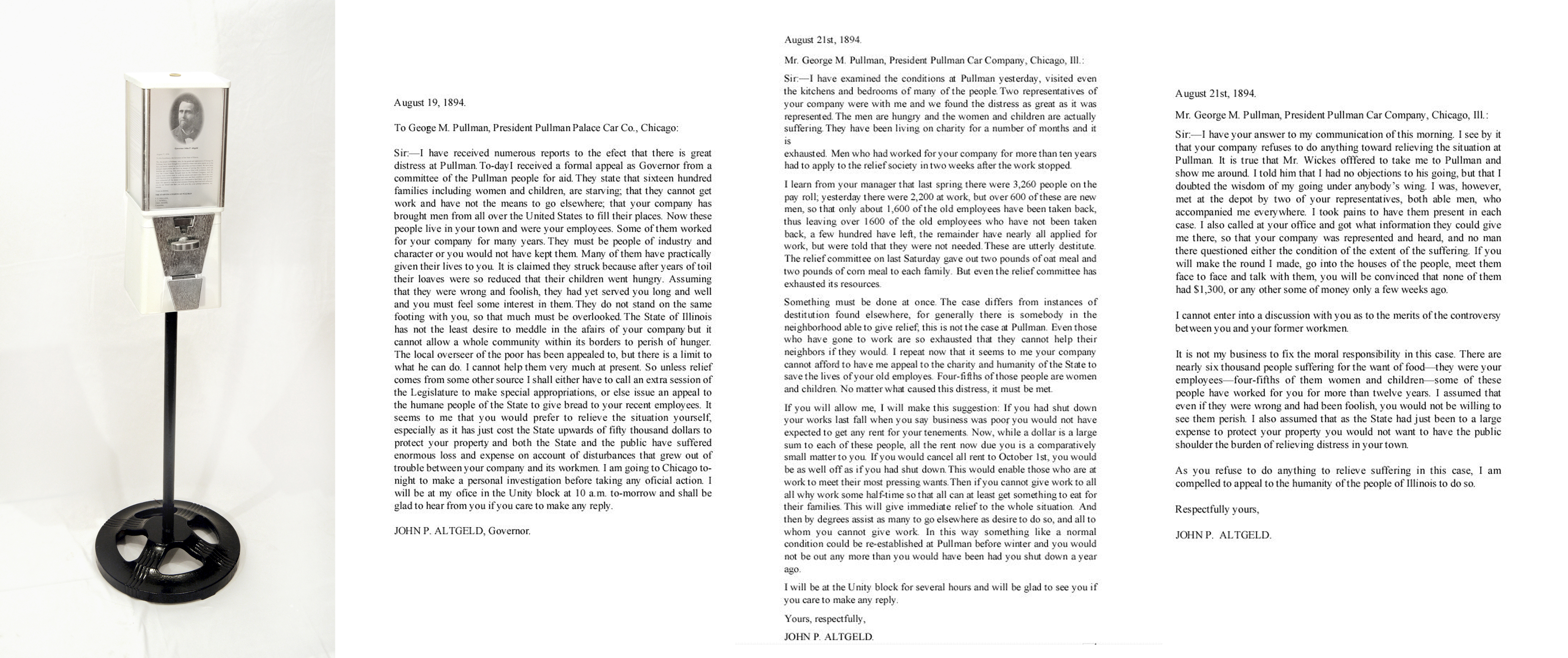

Title: "Altgeld - (The Altgeld Letters)" Dimensions: 44" x 14" Assembled objects: Gumball machine, 1894 pin, four letters Interactive I’ve asked friends, authors, historians, scholars, activists, laborers and labor leaders to write something related to each piece in the project. I am so appreciative of each and every one of them for their contribution. Illinois poet Vachel Lindsay (1879-1931) christened Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld (1847-1902) as the Eagle Forgotten. The others that mourned you in silence and terror and truth, The widow bereft of her crust, and the boy without youth, The mocked and the scorned and the wounded the lame and the poor That should have remembered forever, remember no more. Every generation expects great things from its elected leaders – moral leadership and high values. Few deliver – but John Peter Altgeld delivered and then more, suffering blistering scorn from the editorial pages and the elites for his outspoken stances. Born in Germany his parents immigrated and farmed in Ohio. Altgeld served in the American Civil War. He studied law while working on the family farm and roaming westward as a railroad laborer. He passed the bar in Missouri in 1871. He 1875 he moved to Chicago, establishing himself as a lawyer yet gaining his fortune in real estate, including building in 1893 what was then Chicago’s largest structure, the Unity Building. History books place the “Progressive Movement” in the early 20th century. It was a heady time, with labor organizing, women’s suffrage, urban reform, civil rights and other movement challenging the Gilded Age’s accumulation of wealth for the few at the expense of the many. The Progressive Movement had its first flowering in Illinois during Altgeld’s 1893-1897 one gubernatorial term. Child labor laws, factory inspection, prison reform and expanded public education all marked his administration. Women were appointed to office, including Florence Kelley as the state’s first factory inspector. Altgeld’s courageous stands, which ended his political career, were two significant acts. In 1893 he re-read the 1886 Haymarket trial and pardoned the three men still in prison, scolding the trial as totally unfair and calling the evidence presented “pure fabrication.” The conservative Chicago Daily Tribune linked Altgeld with the predominately German immigrant defendants as a secret socialist. The newspaper wrote on June 27, 1893, about Altgeld: “The Anarchists believed that he was not merely an alien by temperament and sympathies, and they were right. He apparently does not have a drop of true American blood in his veins.” Altgeld knew the pardon would doom him politically but he stood by his principles. A year later he was again embroiled in controversy as the nation sank into economic depression. The Pullman boycott and strike was centered in Illinois. Altgeld pleaded with George M. Pullman to negotiate, which Pullman refused. The railroad companies were begging for federal troops to break the strike. Altgeld wrote his fellow Democrat, President Grover Cleveland, forthrightly saying Chicago and Pullman were calm, no troops were needed. The President ordered troops in and violence broke out. The troops, U.S. Marshals and the federal courts quickly broke the strike. Altgeld accused U.S. Attorney General and railroad attorney Richard Olney for establishing for “a new form of government never before heard of among men; that is government by injunction.” In August, Altgeld wrote to Pullman and asked him to forego past rent from the strikers, a plea ignored. On August 20, 1894, Altgeld went door to door in Pullman, documenting for himself the community’s conditions. He wrote to Pullman, reminding the sleeping car magnate that the State had spent considerable funds providing militia to protect his property. Altgeld noted, “The men are hungry and the women and children are actually suffering. … They are utterly destitute.” Altgeld suggested that Pullman relieve back rent payments through the coming October, writing, “Now, while a dollar is a large sum to each of these people, all the rent now due you in a comparatively small matter to you.” He suggested that Pullman at least employ former workers half-time, “so that all can at least get something to eat for their families.” Pullman failed to follow the Governor’s suggestions. Condemned for his Haymarket pardon and his anti-corporate views, Altgeld was defeated for a second term in 1896. 1896 was also a Presidential election year. Altgeld led the reform faction against Cleveland’s re-election, supporting populist William Jennings Bryan as the Democratic candidate, who was defeated by Republican William McKinley. Although losing, Altgeld out polled Democratic presidential candidate Bryan by 10,000 votes in Illinois. Former railroad attorney, now civil liberties and worker advocate Clarence Darrow invited Altgeld to Darrow’s law firm. Suffering ill health, Altgeld lost all his properties and was financially supported by Darrow. On March 11, 1902, speaking to an anti-British imperialism rally in Joliet, Altgeld suffered a cerebral hemorrhage and died at age 54. Thousands filed past his body at the Chicago Public Library and Hull House’s Jane Addams and Darrow eulogized him. He was buried in Chicago’s Graceland Cemetery, also George Pullman’s final resting place. The Eagle Forgotten is often most remembered for his valiant Haymarket pardon and his staunch opposition to militarizing the Pullman strike and boycott. Under Altgeld Illinois was the “laboratory of democracy” where the Progressive movement first flowered, leading to safety and human rights reforms which were foundational for human improvement and uplift. *Mike Matejka is the retired Grand Prairie Union News editor, which served working people in central Illinois. He was also the Governmental Affairs Director for the Great Plains Laborers District Council, covering central Illinois, Iowa, Nebraska and South Dakota. He is a board member with the Historic Pullman Foundation, Illinois Labor History Society and the McLean County Museum of History. He has written extensively on labor and railroad history. He lives in Normal, Illinois. Read the Altgeld letters: Here

|

The Gumball Project |

other ART sites design by: t a l l s k i n n y . c o m